Any visitor to the Baltimore Museum of Industry will likely recall how it invites guests to discover Charm City’s industrial past through a simulated oyster cannery, pharmacy, garment loft and food processing gallery.

In October, the museum installed its newest exhibition, “The Neighborhood Corner Bar: A Baltimore Story 1870-1920.” Curated by Rachel Donaldson, the exhibition will be on permanent display at the BMI, at 1415 Key Highway in Federal Hill.

Unlike many of the BMI’s other exhibitions that focus on production, the new installation “looks at consumption and the development of working-class culture and working-class communities,” says Donaldson. “We have so many corner bars and remnants of corner bars because they were directly financed by breweries [in Baltimore].

“Especially after the rise of immigration after the 1848 revolutions [in Europe], you had many small independent breweries, and they’re all competing with each other,” she says. “And they thought they could do better by going directly to consumers. So they either opened their own bars — a system called ‘the tied house’ — or they had exclusive distributor contracts with bars. In these different bars, you could get different types of whiskey, but only one type of beer.”

In an online description, the typical corner bar is characterized as a “wooden bar with a brass rail and a mirrored cabinet in the rear, both flanked by historic beer advertisements, sample menus, and photographs — many of them donated by local family members of past bar owners during community collecting events held around the city.”

Text panels hidden inside mirrored cabinets provide historical information about corner bars in the context of the social and cultural norms of the era.

“This was a time when these neighborhood bars were referred to as ‘workingmen’s clubs,’” says Donaldson. “In the late 19th century, fraternal organizations and men’s clubs were all the rage. So [corner bars] were places for working-class men to have that same kind of club-like atmosphere to play card games, get news about sporting events. … This was not an era of barhopping. You would have your bar and you would go there regularly.”

In those days, women were not welcome at neighborhood watering holes, but they were permitted to enter through side entrances where they could purchase beer to go. Women also took advantage of the bars’ free lunch programs where they could “come in, get their lunch from the edge of the bar and then go straight to the back room,” says Donaldson. “Men wouldn’t go into the back room space during the lunch hours.”

The exhibition also touches on racial discrimination in corner bar culture.

“If you were a person of color trying to go into a white ethnic bar, you could face very violent ejection,” says Donaldson. “So you have the development of drinking establishments for Black working-class Baltimoreans. But that history follows a different trajectory. Those tended to be more like what we think of as Southern juke joints, where they served both men and women and had more live music.”

‘Have a Drink’

Dundalk resident Troy Pritt is proud that his great-grandparents never turned away Black customers from their Gilmore Street tavern, even during the Jim Crow Era.

“[His great-grandfather] said the only color in this world that matters is green,“says Pritt. “If somebody works hard, they deserve to be able to come up to the bar like everybody else and have a drink.”

A former steel worker who now works as a senior human resources business partner at LifeBridge Health, Pritt grew up knowing about his great-grandparents’ bar but not that he was of Jewish ancestry.

Pritt discovered that tidbit of information about a decade ago when a long-lost cousin in Florida informed him that his great-grandparents, Max and Bessie Kaminkow, were both Eastern European Jewish immigrants. (Pritt’s grandfather was also Jewish but married a non-Jew after World War II and never spoke of his Jewish heritage.)

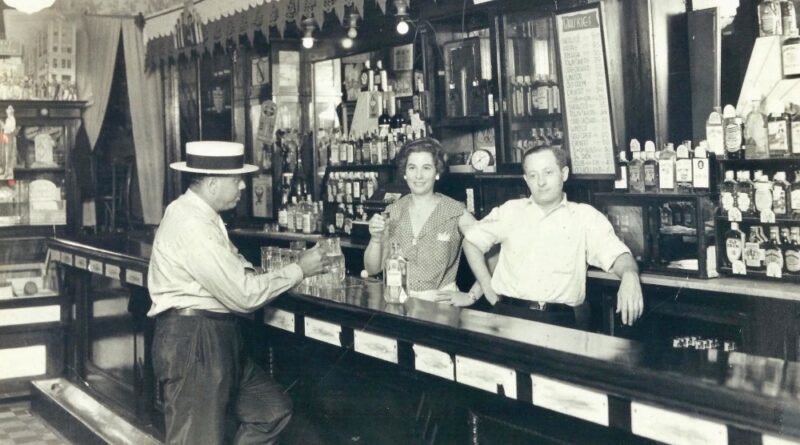

As part of their correspondence, Pritt’s cousin sent him a photograph of his great-grandparents in their bar. When learning of the BMI’s new exhibition, Pritt reached out to the museum to lend the image. Pritt says it will be among a collection of photos “on rotation” in the gallery.

Pritt says the building that housed his great-grandparents’ bar still stands.

“The family lived over top of the bar,” he says. “The folklore I have heard is that they bought it during Prohibition and got it very inexpensively. Many said my great-grandmother could make bathtub gin. Evidently, they kind of ran this as a speakeasy and then opened it up as a legitimate bar after Prohibition.

“The other side of it was a confectionery where they had candies and little wrought-iron tables,” Pritt says. “One cousin still has the price list from the bar that was handwritten by my great-uncle Abe, who had great penmanship, and another cousin has the wrought-iron tables and the milkshake machine that was in this confectionery.”

Pritt regrets not knowing about his Jewish heritage sooner in life. “I never heard my grandfather ever mention his father or his mother,” he says. “He was just a very quiet man and did not share a lot. Which is a shame, because there are so many things I’d want to ask him today.”

For information about “The Neighborhood Corner Bar,” visit thebmi.org.